- Home

- Stephanie A. Smith

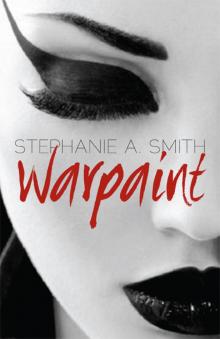

Warpaint Page 15

Warpaint Read online

Page 15

“All right. All right. But why smoke? You can’t tell me smoking and riding go together like a horse and carriage?”

Quiola fidgeted with the string ties on her jacket, and didn’t say anything.

“Hmm?”

“No, not exactly. I – ” she shook her head. “You’re right. I should quit.”

“Why in heaven’s name did you start?”

“I don’t know. It just happened.”

“Oh, bullshit,” said C.C., slamming an open hand down on the mail she’d just placed on the table. “I see what you’re doing, and I don’t like it one bit. Courting death. That’s what it is. I’ve had my brush, and now you’re courting it. Of all the crazy idiot things to do to me, Quiola.”

“Courting death? No I’m not.”

“Riding. Smoking. What’ll it be next, sky-diving?”

“I’ll stop.”

“Which? Riding or smoking?”

Quiola glared. “Smoking, all right? Smoking.”

C.C. closed her eyes and put her hand to her forehead. “Go home, Quiola. Please. Just go on home.”

♦

When the Christmas holidays of 1944 had passed, and the children went back to school, Ted Davis’s teacher became so concerned about the boy’s behavior, he asked to meet with Dr. and Mrs. Davis.

C.C., only seven, didn’t quite understand and she told Liz that she was –

“– scared.” It was a cold, cold February morning. Liz was still dozing in the guestroom, having come out the night before from the city after she and Paul had quarreled so she’d asked Nancy, you know, with the new baby and all, if she might need any help around the house?

C.C. climbed up on the bed, and Liz rolled over. “What are you scared about?” she said, turning back the quilt so C.C. could crawl in.

“Everything.”

“Oh, no, not everything!”

C.C. nodded. Her unbraided hair, wild, stood out like a blond halo around her head. “Everything’s so hard.”

“School?”

“Yeah.”

“What grade are you in?”

“Aunt Liz, why do you keep forgetting?”

Liz laughed. “Because I’m old.”

“Oh, well. Second grade.”

“I see. Reading? Math?”

“I like reading. Math is yucky, and I can’t tell time. I just can’t.”

Liz patted her arm. “You will. Just give yourself a break.”

C.C. made a face, then said, “I’ll tell you a secret. A secret secret.”

“Ah.” Liz folded her hands under her head. “I’m ready.”

C.C. elbowed up to look into Liz’s face. “You promise not to tell?”

“That’s our deal, isn’t it? With secret secrets.”

C.C. flopped back down. “Okay. I was mean to Tucker, when Mom first brought him home. I didn’t want another brother. I have one.”

“I know. But he’s a cutie, isn’t he?”

“Now he is. When he was littler, he was all red and scrunched up.”

“All babies are like that. You were red and scrunched up.”

“No I wasn’t.”

“Yep.” Liz rolled a curl of C.C.’s hair around her finger letting her finger slide through the curl. “I hope you weren’t too mean?”

“I pinched him. Hard. When nobody was looking. I made him cry.”

“Did you stop?”

“Yeah. I got used to him, and then I felt bad ’cause I was so mean.”

“Ah, you weren’t too mean. Besides, you said you stopped. He’s so little, he won’t ever remember.”

“I know. But I still feel bad.”

“Well, you told me, didn’t you? So you don’t have to keep your secret-secret all bottled up.”

“I guess.”

“That’s not the problem, is it?”

“Maybe.” She shrugged, staring at the quilt’s pattern. “Aunt Liz? What would be really mean, to do to a baby? Pinching’s not so bad. What would be really bad?”

“A lot of things. Babies depend on us. You see how your Mom and Dad take care of Tucker – or me, if I’m holding him we are, all of us, very gentle, very careful. Why? C.C.? Come on. What’s the real secret-secret you haven’t told me yet?”

“I’m scared,” she said, her voice down to a whisper.

“Of everything, you said so three minutes ago. Everything and what else?”

“Ted.”

“Ted? Why?”

“He hates Tucker.”

“No he doesn’t. I’m sure.”

“Yes he does. He told me. He told me he was going to get rid of him. He said Tucker had an evil eye, and we had to protect Mom.”

“Oh, bother,” said Liz, more to herself than to C.C. “And just how was he going to get rid of Tuck?”

“I don’t know,” she almost wailed. “That’s why I’m scared. And then his teacher called – maybe Mr. Gentry found out. What will they do to Ted, for being so mean?”

“Hmm. You know I haven’t talked to your mother about that meeting yet.”

“Don’t tell her I told you! Ted would kill me.”

“Honey, calm down. I don’t go back on secret-secrets. But if Ted’s teacher is involved, then maybe it’ll all just be over, and your secret can be buried in the back yard, with that other one we fixed. Just let me talk to your mother first, okay?”

“Okay.”

♦

Seated on Dr. Shea’s examining table, dressed only in a blue paper gown, C.C. drummed her heels lightly against the cold stainless steel, waiting, waiting. When someone knocked on the door, she said, “It’s okay. I’m ready.”

Dr. Shea came in, with a thick manila folder under one arm. “How are you?”

“Good. Fine. How are my x-rays?”

“I just want to take a listen, first.” She put the folder on her chair, adjusted her stethoscope, and gently folded back the paper gown. “Take a deep breath? Out. In? Good. Another? Out. Good.” Dr. Shea hung the scope around her neck and sat down, laying the folder in her lap. “I’ve got bad news, I’m afraid.”

C.C felt as if her oncologist had just socked her in the mouth. “But the x-rays were routine, weren’t they? What could be bad about my lungs?”

“I’m sorry to have to tell you this, but the breast cancer has metastasized to one of your lungs. I’m surprised because you’ve responded so well to the Herceptin, I just didn’t think – but I have to help manage your emphysema, too, and when I saw the pictures, well, I called in a radiologist, to be absolutely sure. We need to talk about your options –”

“Options? No – wait, wait. I can’t. I can’t do this. I can’t – I need time. Not chemo again. My hair just grew back!” she said, grabbing a handful of it. “Fuck.”

“I know. I know. Did somebody come with you today?”

C.C. shook her head.

“Shall I call your friend? I don’t think you should be alone.”

“I don’t want anybody. Not yet.”

“Shall I just tell you what course of therapy I think you should follow?”

C.C. crossed her arms and her ankles, rocking herself gently. “No. I want to ask you first, point blank: can you cure it? Will I ever be cancer-free?”

Dr. Shea’s whole face softened with regret. “No, C.C. All I can do is try to control it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t live a full life. That’s what I’m here for: to help you survive, to keep you comfortable, to help you make the most –”

“Stop. Please just stop it!”

“Are you sure I can’t call your friend? I really think –”

“No. I need to be alone. I need to think. I don’t have to decide right this minute, about anything, do I?”

“Not right this minute, but soon. Give me a call in the next few days.” She took a card from her front pocket, and wrote on the back of it. “That’s my cell. Don’t hesitate to use it, bypass the office get straight to me. As soon as you can? Please? You’re sure you’re okay to drive?”

“

Yes. I am, thanks. I’ll call. Soon.”

Dr. Shea nodded, and left the room, closing the door softly behind her. C.C. stared into space for a few seconds, then shook herself and began to dress. Somehow, she got out of the office, paid her co-pay, and drove herself to the “shed” where she sat down on the couch, shivering and sweating.

“Fucking crab,” she muttered and then shrieked, a long, loud mad sound that made her own ears ring.

9. Return of the Crab

When C.C. showed up at the condo late that afternoon, Quiola was deep into packing for another move; open boxes, stacks and balls of newspaper, twine, tape and in amidst it all, the cat.

“She’s been in kitty heaven,” said Quiola.

“So I see. You’re making good progress here – better than I’m doing with the “shed”. But I just called some local movers to finish for me.” She sat down on the edge of the couch. “There’s no good way to put this, so I’ll just say it: the crab is back. I thought it was a routine x-ray for emphysema.”

Quiola turned away from an open box. “What emphysema?”

“Dr. Shea says I’ve a touch of emphysema. I don’t believe her – it’s just a cough.”

“What do you mean you don’t believe her?”

“How could I have emphysema? I smoked, okay but only a little, for maybe three years. Doesn’t make sense. Emphysema’s for the hardcore.”

“You didn’t believe her? You didn’t believe your own doctor?”

“Oh, who cares? The cancer is back. Fucking crab. Here I thought I’d beaten it off with a stick. What am I going to do?”

Quiola sat down in the middle of the messy living room floor, then laid flat on her back, on the cool hardwood and took several deep breaths, while Amelia curled up on her belly. C.C. slid off the couch and onto the floor with them both.

“Where is it back?”

“In my lung.”

“When did you find this out?”

“Today. This morning.”

“And the emphysema?”

“Just before the surgery. But I still don’t think –”

“I don’t care what you think,” said Quiola rolling onto her side, spilling the cat. “And I’ll tell you one thing. You are not going to any doctor’s appointment alone again. Ever. I intend to stick to your side like glue. Emphysema is a disease, not an article of faith. What would your father have said?”

“Doctors make mistakes, too.”

“X-rays don’t.”

“Yes they do if they aren’t read –”

“Enough!” Quiola got to her feet and walked out.

♦

Having planted, like so many Americans, a victory patch to support the troops during the War, the Davises continued to grow fresh peas, beans, chives, basil, corn, so when Liz took C.C.’s hand and headed into Nancy’s summer garden, it was full to bursting with flowers, early vegetables and sprouts of what would soon become the late summer crop.

“You have it with you? Yes?” Liz asked. “Good. Shall we bury it next to the other one or find a new spot?”

“Next to the other one. Mom said we could pick flowers for the dinner table.”

“Lovely. So, do you remember where we buried the other one?”

C.C. pointed at an apple tree that sat between the pear and cherry trees.

“Fine.” Liz moved past the black-eyed susans, the peas and beans until she stood with C.C. at the foot of the apple tree. She put down her basket of gardening tools. “Pick a spot,” she said, as a yellow butterfly zigzagged by. It was just after lunch, and the sun showed signs of muscle, so that after Liz had put on her gloves, knelt on one denim knee and had been digging for a while, she worked up a light bead of sweat. C.C., dressed that day in a crisp jumper, watched and fingered the piece of paper in her pocket.

“There,” said Liz. “that should be deep enough. Hand it over.”

C.C. withdrew the paper from her pocket, and looked at the words, then turned her blue eyes up at Liz. “It will be gone, won’t it?”

“All gone. I promise you, Ted won’t hurt Tuck. When a person buries a secret-secret, it’s all over. The other one didn’t come back, did it?”

“No.” C.C. held out the piece of paper. “Ted is okay?”

“He’s fine. He’s just a boy, that’s all. Boys are funny. They like to scare girls. They like to stir up trouble. Ted just wanted some attention, that’s all. He got it and it’s over.” She mounded dirt on top of the secret-secret, written out on the paper, and got off her knee, brushing dirt from her jeans. “Feel better?”

“I do. I really do!”

“Told you.” She shook off the spade, adjusted one glove and selected a pair of shears. “Carry the basket?”

“Okay.” C.C. took the handle. “Mom said black-eyed susans, yellow daisies and the larkspur.”

Liz stared out across the garden. “Really. You mother has her ideas, doesn’t she?”

“Yep. Like when she cooks, too. If Daddy cooks dinner, you never know what will happen. Like when Mom went to have Tucker. Daddy made us dinner, and it was steak and onions with fried potatoes. Can you believe it?”

“But that sounds yummy! What’s wrong with it?”

C.C. laughed so hard she almost dropped her basket. “Oh, Aunt Liz, of course it was yummy. Daddy’s dinner is always yummy, but it’s wrong, don’t you see? Because you don’t make steak with fried potatoes, steak goes with baked, or maybe twice-baked.”

“Oh, I see. Your mother does have rules, doesn’t she? And what’s the plan for tonight?” She began to cut black-eyed susans, laying them on one side of the basket.

“Soft-shelled crab, coleslaw, peas, bread and butter. I like that. Do you?”

“Peas when they’re fresh. Crab, always. Especially soft-shelled ones – and your Mother knows it, too.”

“Yep. She said it was because of your show you’re having in the City.”

Liz half-smiled. “Not much of one, but your Mom is an optimist.”

“What does that mean?”

Liz leaned over the larkspur, and cut a bunch. “It means she has faith in me. She thinks I’m a good painter.”

“You are! I know you are!”

“Thanks, honey.” Having cut the flowers Nancy wanted, Liz put the shears away and took the basket from C.C. who asked, “Want to see the crabs? Dad has them in an ice bucket in the pantry. I think they look like big bugs. Don’t you?” She shaped her hands like claws. “When they wave their arms and made them go like this?” She made a clamping motion with her clawed fingers. “Big bugs from the sea. But I’m going to eat them up before they can eat me!”

♦

Parker Moore moved with slow deliberation from one hive to the next, his bee veil, a sheer cloth that he’d had his wife sew to an old hat, closed, checking that no moths had been about, wreaking havoc with his swarms. Around the turn of the century, he’d switched from his inherited, old-style hives to the Langstroth modern ones, which had, in only one season, doubled his local profit. Pleased, he’d added to his apiary until he had about a two-dozen colonies.

“Father?”

Parker turned toward the voice of his youngest daughter who stood at a distance, arms folded across her chest, her light summer dress a size too big, a hand-me-down from her sister, Anita. With her sun-darkened skin and light eyes, she was a handsome girl, too handsome for her own good, her father thought.

“What does your mother want?” he said impatiently.

“She says you got to talk some sense into your son.”

Parker turned back to his hive. “Tell her I’m busy.”

“But he’s gonna enlist.”

This made Parker Moore straighten up. Taking his daughter by hand, yanking his veiled hat off, he nearly dragged Lizzie across the farm, marching, at a good clip, away from his bees, past the far barn, the near barn and in through the back screened door of the house, which he slammed.

“What the hell nonsense am I hearing?” he shouted at his eldest a

s he made his way from the kitchen to where Parker Junior – called Park – stood, beside his mother.

His son stiffened, and looked his father square in the eye. “I’m going over.”

Sara Moore, seated at the dinner table, wore what Liz thought of as “Mother’s stone-face.” Her thin-lipped mouth set in a straight line, her blue eyes hard as marble, she shook her head. “Father, your son has lost his mind.”

“No,” said Park. “I have not. I’m a man. My country is at war. I know my duty.”

“Your duty?” said Parker. “Your duty is to this family and this farm, not to some idiot in a Southern swamp. We’ve got troubles enough here without you running off to fight in another man’s quarrel. Let those foreigners solve their own problems.”

“But it is our problem. The Lusitania –”

“– was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Don’t dump Wilson’s garbage on me, boy.”

“You voted for him.”

Parker became very still as the young man spoke, eye of the hurricane still, which made Sara clasp her hands. Lizzie started edging over to the kitchen. The silence did not break until Parker at last intoned, with the finality of an ax-stroke, “You have work to do. So do I.”

“Father –”

“Did you hear me? Jo shouldn’t have to muck out all three barns by himself.”

Park said nothing. He glanced at his mother, then turned on his heel and marched past Liz, out the kitchen door.

“Wait!,” the girl said and hopped out the door after her brother, caught up and jogged along beside him. “You’re not going to go, are you, Park? You’re not gonna leave us?”

“Just watch me. Just you wait and see.” He raised his voice as they neared the barn. “Jo? You in there?”

Liz stopped dead, letting her brother hurry on. She watched his back, blinked, watched and then murmured. “He is going. He’s going all right.”

♦

Quiola unbuckled the noseband and throatlatch, scooped her hand under the crownpiece, and encouraged Splash to relinquish the bit. Slipping on his halter, she cross-tied him, hung up the bridle

where Mike could see it, and unbuckled the girth. Splash stood quiet, watching.

Warpaint

Warpaint