- Home

- Stephanie A. Smith

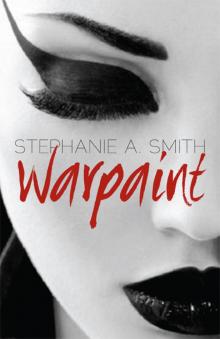

Warpaint

Warpaint Read online

Table of Contents

PART I: RETROSPECTIVES 1. Three Lives

2. The Opening

3. Silences

PART II: BEAUTY AND THE BREAST 4. Poison

5. Run Away

6. Make-Up

PART III: TREATMENTS 7. Change

8. Flinch

9. Return of the Crab

PART IV: SWAN SONG 10. To Be Gracious, and Seem Happy

11. Meig's Point

12. Lutsen

Warpaint

THAMES RIVER PRESS

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company Limited (WPC)

Another imprint of WPC is Anthem Press (www.anthempress.com)

First published in the United Kingdom in 2012 by

THAMES RIVER PRESS

75-76 Blackfriars Road

London SE1 8HA

www.thamesriverpress.com

© Stephanie A. Smith 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All the characters and events described in this novel are imaginary and any similarity with real people or events is purely coincidental.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-85728-200-2

Cover design by Laura Carless

This title is also available as an eBook.

* * *

This ebook was produced with http://pressbooks.com.

PART I: RETROSPECTIVES

1. Three Lives

A famous anthropologist and a very old friend of the Davis family once called the artist Liz Moore a witch. “I mean a real one,” he said on an August night in 1947 out on Montauk Point. Once the War had ended, the Davises took pains to reconnect with old friends, like Al Kroenen, who’d himself made it back from hell. That evening the weather, so miserably hot and close for a week, lifted a bit. The setting low-angled sun caught in frosted martini glasses and flared.

“One of yours, Tom?” asked the anthropologist, gesturing with his sweating birdbath at a large painting hung over the granite hearth, a canvas of floating amoebic shapes, crimson with ruby centers fading outward to a shimmer of rose-ochre on a background of textured gold-leaf.

“That? Oh no,” replied his host. “I only paint sea. That’s –” he broke off, having glimpsed a stride across the rise of his lawn. “Here’s your artist, Al.” Tom put down his drink to greet the woman who stepped in from the screened porch of the converted farmhouse. Oddly dressed in a man’s cotton shirt and denim pants, she was lithe and switchblade thin and wore her straight black hair in a bob.

“Liz,” said Tom to the new guest. “Glad you could make it! I’d like you to meet Al Kroenen – Al, Liz Moore. Al was asking after your painting, my dear.”

“Oh? Which one?” she asked, having given the Davises three: a small self-portrait for the sitting room, two abstracts for the formal living room.

“That,” said Al, gesturing again with his martini at the vivid amoeboid shapes that seemed as if they might, at any moment, untether themselves from the canvas and levitate, to mingle on the warm air amongst the guests.

“Wirkorgan,” said Tom. “It’s called Wirkorgan.”

“Oh that,” said the painter, glancing up at Al with large, slanted, olive green eyes. “A commission from the good doctor. Do you like it?”

“Impressive,” he paused, at a loss. “Different.”

“It’s just a painting,” she said flippantly, turning to Tom. “Where’s Nancy?”

But before Tom could locate his wife, a child with thick-curled, fuzzy blond hair flew over the threshold. “Dad!” she cried. “Dad, Ted won’t let me –” and that was as far as she got because Liz, in farmer’s denims without shoes, left the girl dumbstruck. She knew their neighbor-lady-artist was weird, but blue jeans and bare feet at a dinner party?

Mrs. Davis appeared, a small, sturdy brunette in a proper summer dress, pearls and perfume. She carried a tray of hors d’oeuvres. Al’s wife, Patricia, large, blonde and mild, followed with a basket of crackers.

“Charlotte Clio,” said Nancy Davis sharply to her daughter. “How impolite. Close your mouth and say hello to your Aunt Liz.”

“Hello Aunt Liz.”

Tom laughed. “That’s better. Now, Charlie, tell me: what won’t your brother ‘let you do’ this time?”

C.C. sidled up to her father, bent him down by his elbow so she could whisper, and kept her eye on the gangly, bare-foot guest to whom Nancy handed a glowing birdbath. Liz took a sip and then, quick as a wren, zeroed in on C.C.

“Honey,” she said, her eyes alight. “You’ve seen my bare toes before. I didn’t grow an extra.”

“Yes, my goodness, C.C!” said Nancy. “But here, now, you two haven’t been properly introduced – Liz Moore, Pat Kronen. I take it you’ve met Al?”

“He’s been admiring my work,” said Liz, gazing at Pat, who smiled wanly and asked, “What work?”

“That painting over the fireplace. Nance, where’s Tuck?”

“Upstairs, asleep,” she said, setting various painted china plates of delicacies on the coffee table. “Try a deviled egg, Liz? Caviar?”

“Tuck’s asleep already?”

“Yes, and thank goodness.” Nancy patted a permanent wave back in place. “He’s getting to be such a handful. Al, Pat – did Tom tell you what sort of mischief Tucker was up to last month while we were down in Florida?”

“No,” said Pat, her eyes still fixed on Liz, who had quit the adults and was folded onto the oval braided rug with C.C. Just then, Ted Davis, curly as his sister but dark like his mother, ran in, looked around, hitched up his pants and said:

“Dinnertime!”

“Not yet, young man,” said Dr. Davis. “Come here. We need to have a little talk.”

“So what happened?” Al asked Nancy.

“Tuck gave his father quite a scare,” she said.

“And you, Mother,” Tom shot back.

“Oh, yes, of course, but it all happened so fast, the alligator was back in the lake before I even knew it had been out.”

“’Gator?” said Al, taking a pipe from his pocket. “Mind if I smoke, Tom?”

“No, go ahead. Matches are in that metal sconce near the fireplace – see them? Now Ted, your sister tells me…” at which point he lowered his voice.

“This is a match?” said Al, examining one he’d taken from the sconce. “I could burn down Rome with this thing. So? What ’gator?”

“My younger son,” Tom said, turning away from Ted, “decided to tease one. ’Bout this long,” he held his hands as wide apart as he could, “and fast. I had no idea those things could run.”

“Tuck was faster,” said Liz, “but only a snack, for a ’gator. Dollop of ice-cream.”

Perhaps Liz’s sang-froid that night provoked Al’s judgment – or her indifferent response to his admiration for Wirkorgan, or something about her dark face, but Al, being then a very famous anthropologist, something, indeed, of an expert on Indians and shamans and such, was believed when he said, in a decided tone after Liz had left –

“Your artist, Tom, is a witch.”

The two couples were settled in the sitting room, one floor lamp-lit, which made the gold in Wirkorgan simmer.

Tom poured a cognac for his wife, as Pat Kronen said to her husband,

“Darling, that’s nonsense. She’s a white woman from Minnesota, from the North Shore of Lake Superior. That’s what she told me, at dinner. Farming people.”

Al shook his head and sucked on his pipe. “Several bands of Ojibwe live along the North Sh

ore.”

“Thanks, dear,” said Nancy, as Tom handed her a drink. She looked at Al. “I’m afraid there’s no Indian in Liz,” she said. “Norwegian, Hungarian, Scots, with a little English thrown in.”

Tom patted Nancy’s shoulder. “Well, Al, what kind of a witch is our Liz?” he asked. “Good or bad?”

“Tom, really,” said Pat. She tugged at the bottom of her blue dress a little, and crossed her ankles. “Don’t encourage him.”

“As I said, a real one,” said Al quietly.

Tom sat down on the floral arm of a loveseat. “Meaning?”

“She has force, a power. Most whites ignore it. My people cultivate it.”

“She’s a force, all right,” said Nancy, smiling. “A force of nature.”

“You mean like a witch-doctor?” Tom asked.

“If you like. Watch her. She’s remarkable – and talented. But not dangerous, I should think.” Al blew out thick shag smoke. “At least not to herself.”

Tom believed him. So did Nancy in a certain way and a rumor fired up, spread around, ran to the City and settled in the Village. Liz Moore was a witch. When Liz did nothing to quash it, what started off on cocktails and cognac solidified into fact and would remain a fact to the day Lá Moore died.

But in April of 2002, Liz Moore, ninety-four, internationally famous, was very much alive, and en route from her estate – once her mother’s home – in Lutsen, Minnesota, to New York City for a retrospective at MoMA, a send-off for the fifty-third-street location, closing that May for renovation. While East, Liz was going to visit C.C. Davis, who was, of course, no longer a tow-headed child, but a woman in her sixties.

Sitting in her own Connecticut living room with her long-ago lover, Quiola Kerr, C.C. said, “Liz’s work has the magic, but I’m not sure about her.”

“No kidding.” Planted smack in the middle of a squat black sofa, Quiola glanced at a portfolio of C.C.’s new work, laid flat on the cedar chest in front of her.

The older woman nodded. “That anthropologist used to come and stay over with Mother and Father, every summer when I was a kid. He was bald. His wife smiled a lot.”

“Al Kronen was a very important scholar. I’ve read a lot of his writing.”

“Yes, yes he was… special. For one thing, he didn’t call Indians lazy or drunks or dirty, like most folks did back then. Conquered, he said. Subjugated by an indifferent people, a ruthless people, a people with no empathy. Us. He was adopted by one of the California tribes.”

Quiola looked up. “Which tribe?”

“Honestly, Quiola – this was something like fifty years ago, now.”

“Just curious. You remember the name of your mother’s perfume from those days. What did you call it? Joy?”

“Of course I remember that,” snapped C.C. “She’s my mother. And I also remember your grandmother’s tribe. Ojibwe. I didn’t mean to offend.”

“Anishinaabeg,” murmured Quiola.

“What?”

“I said no offense. And yes I would like coffee, sweet and black.”

C.C. laughed. “Mind-reader.”

“Maybe. I see you’re working in oil again.”

C.C. nodded an answer, and stepped from the living room out into the kitchenette of her studio, her “shed” as she called it, an old caretaker’s home on a Connecticut estate, tiny, except for the converted attic-loft, where she worked and slept. Returning with their coffee, she said, “Oil suits me. The latest is unfinished and I’m having the devil of a time with it – when you look at it, you’ll see why. So? What have you been doing?”

“Watercolor. Some acrylic. Pottery on occasion, too, when I can get kiln space.”

“Really? Liz Moore won’t approve. Do you think she’s arrived yet?”

“Her flight should have landed at noon. If it wasn’t delayed, she should be at the Plaza by now.”

C.C. took a quick peek at an antique clock. “MoMA paid for the limo?”

“Of course, but I wish she would have let me fetch her.”

“Oh no, not Liz.” C.C. put both elbows in her hands, a characteristic gesture. Compact and wiry like a terrier, C.C. Davis never seemed to add or “shed” a pound. She looked almost exactly the same as she had a quarter-century ago, except for a few more lines and the fade of a blond, snowing to white.

“Liz likes being a stranger,” she said.

“And hates watercolor. Loathes ceramics.”

“They lack strength – according to Liz.” C.C. nipped a glance out the window. That hot, hot April of 2002 had brought up early crocuses at the end of the driveway, along the old rock wall, and as the afternoon sunlight began to turn from midday, their lavender and yellow cups grew dark purple and burnt gold.

“It was always a relief, you know,” said C.C. “to go home, back when we lived on the Island. The trip from the city to Montauk wasn’t always easy, the traffic could get murderous, but calming, you know, like that drive out to Pete and Mark’s in P-town. The road narrows, you can taste the sea. I’d love to go –”

“To Montauk?”

“No, to P-town.”

“Why don’t we, then? I’m sure the boys would be happy to see us.”

“I can’t.”

Quiola’s long, slim, dark hand, hovering above the portfolio, froze. She lowered her fingertips to the edge of the plastic page, then flipped it, asking, “Not even after?”

C.C.’s gaze moved to the floor. “You don’t know how I – how glad I am you’ve come, and how sorry I am to have dragged you here on such short notice, but I wanted to see you, to talk, without static and the Atlantic between us.”

“Oh no. I had a bad feeling –”

C.C. shrugged. “I didn’t want to worry you –”

“You’re worrying me now.”

“Yes, I know, I’m sorry, but the tumor is large, larger than Dr. Shea supposed. I’ve seen a surgeon, a Dr. Wong. She says she’s going to have to take the whole breast, and lymph nodes. I’ll need radiation, chemo –”

Quiola grasped C.C.’s forearms across the portfolio. Smaller than C.C., her gesture took her bodily over the cedar chest. “Breast cancer,” she said, “is curable.”

C.C. laughed and pulled one forearm from Quiola’s tight grip. She laid her hand gently over Quiola’s wrist. “Where there’s life there’s hope, eh?”

“Bullshit,” said Quiola roughly. She let C.C. go, and sat on the edge of the couch, holding onto that piece of furniture as if she might be sucked away somehow. “What exactly did this doctor tell you?”

“I have Stage IV cancer.”

Quiola’s black eyes glistened. “There is no Stage V.”

“No. There isn’t.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I am telling you. Don’t be angry with me. I can’t take it.”

“I’m not, I’m not. I just thought breast cancer was curable.”

“Caught early, it is. But I didn’t notice until the lump was – well, noticeable. Still, I might beat it –” The phone rang. C.C.’s face sharpened, the weight and shadow of her news lifting. “That’s got to be Liz!” she said. Then, swiftly, “When we see her, don’t say anything. She knows I have cancer. That’s enough,” and she scurried to the landline.

Alone, Quiola leaned her head back on the couch and closed her eyes for a moment as a jagged tumble of thoughts jostled past one another: she’ll need help, how could this happen, why didn’t I know, chemo, oh, no not chemo, she’ll… she can’t, I can’t…not again… meanwhile, Quiola could hear the murmur of one side of the conversation, so rather than eavesdrop, she went up the tiny switchback staircase to see C.C.’s latest difficulty.

The studio-bedroom-attic was in disarray. A pile of dirty, rumpled cotton clothes sat in one corner beside a dresser, an unmade futon sat in another. At the far end of the large space stood a long, rough-hewn table covered with misshapen tubes of paint, jars of brushes, palette knives, string, gauze, and towels. In the middle of the table sat a small al

uminum easel, covered by a drop cloth, which Quiola pulled up.

“Hmm. What on earth moved you back to this?” she said.

In the late fifties, C.C. had painted a series called Planets: five long, narrow, subdued oils of three heavy globes, in varying tones, sensuously pungent, so eerily and erotically charged, it caused a minor scandal. And that, it seemed, was that, because – and for no reason she’d ever given Quiola – she turned to a modified, cubist realism, something that irked the boys of New York. She remained faithful to that idiom until 1971 when abruptly she’d turned to female portraits, most in morbid colors, as if the women were corpses.

The difficulty that Quiola gazed at was both new and old – the narrow canvas and the globe-shapes were back, but now in clusters, elongated so they seemed unburst rain aching to fall of thick, palette knife-strokes in gelatinous green pond scum beside cartoon yellow or contusion purple and black.

“What do you think?” asked C.C., coming up the stairs.

Quiola let the cloth drop. “Very personal.”

“Exactly. It’s killing me.”

“Lay off, then.”

“Can’t.”

“No. Of course you can’t.”

“Ready to eat?”

“Sure,” she said, turning to follow C.C. back down the stairs. “How’s Liz?”

“Fine. Wants us to stay with her at the Plaza. Says the suite is enormous.”

“That’s just silly. We can stay in Chelsea.”

“No. Wants us close. Come on, I’ve got salmon to broil.”

“You let her push you around, you know.”

C.C. laughed. “Can’t help it.”

Warpaint

Warpaint